Corn silage production offers a great opportunity to plant cover crops for erosion control and water quality benefits. In Northern climates, cover crops can be hard to establish following grain harvest, but if corn is harvested for silage by late September, grass cover crops can grow quickly and provide valuable ground coverage.

Winter rye is the most popular cover crop in this scenario, as it will survive the winters in the northern U.S. and provide benefits up until termination in the spring. Other popular grass cover crops include oat and spring barley, which can grow quickly during the fall but will die off during the winter. This has the advantage of reducing an extra trip across the field to terminate the cover crop, but the dead biomass may not provide adequate erosion protection in the spring.

Concerns about fall application

Many questions still remain when using cover crops, especially when manure is applied in the fall. While fall applications are essential to overall manure management, application at this time does create risk of nitrate leaching into groundwater or to surface waters via tile drainage. Cover crops can help trap leachable nitrate during the fall and early spring months before planting. We do not expect, though, that this “trapped” nitrogen will be returned to the next corn crop.

The question at hand is how much nitrogen from the manure is left for that next corn crop? In a perfect world, the cover crop would just trap the nitrogen that would be leached, but recent studies in Wisconsin have revealed they also tap into the nitrogen that would be available for the next corn crop.

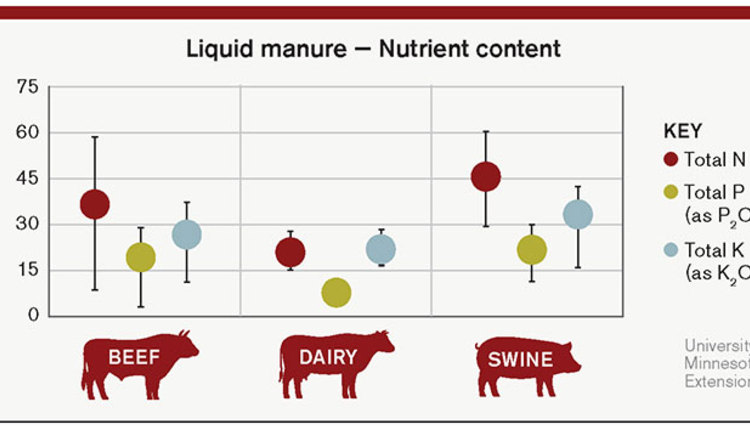

Between 2015 and 2018, cover crop research trials were conducted in Wisconsin at the Arlington, Lancaster, and Marshfield Agricultural Research Stations (located in Dane, Grant, and Marathon County, respectively). In each study year, cover crops (winter rye, annual ryegrass, and spring barley) were planted following a corn silage harvest and an application of liquid dairy manure of about 10,000 gallons per acre, which typically provided about 80 to 100 pounds of nitrogen (N) per acre (lbs./ac).

The different cover crop species were compared to plots where no cover crop was applied. The following year, corn was planted 10 to 14 days after the winter rye cover crop was terminated (spring barley and annual ryegrass winterkilled). Eight rates of N were applied to determine differences in the amount of N needed to optimize corn yields.

Evaluating nitrogen needs

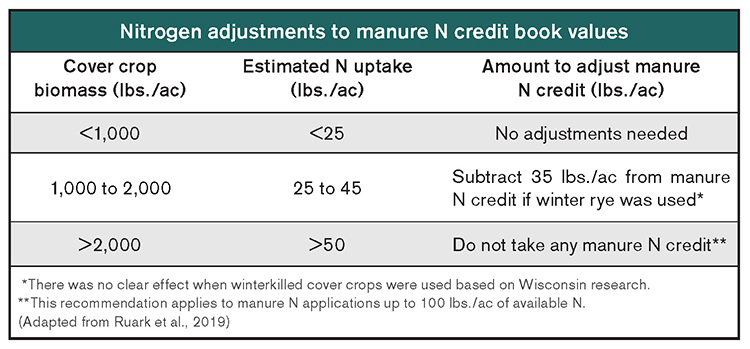

The results of this study revealed three different things. First, if using cover crops that winterkill (such as spring barley), there was no reduction in the manure N credit for the next corn crop. Typically, spring barley produced 1,000 lbs./ac of dry matter biomass or less (Figure 1).

Second, when winter rye (a cover crop that consistently survived the winter) produced less than 2,000 lbs./ac (Figure 2), then about 35 lbs./ac of extra N fertilizer was needed to maximize the next year’s corn yield. This result indicates that the winter rye reduced the “nitrogen credit” of the manure.

Finally, when winter rye biomass exceeded 2,000 lbs./ac, the expected nitrogen value of the manure to the next corn crop was eliminated. This indicates that while getting enough cover crop to provide erosion control (about 1,000 lbs./ac) is good, when the cover crop gets too big it begins to act as a cash crop and utilizes most, if not all, of the nitrogen in the fall-applied manure. Nitrogen adjustments based on cover crop biomass are presented in the table.

Since our research was conducted with the fall applications of manure, we are attributing the need to apply additional nitrogen fertilizer to the fact that the cover crop physically took up a lot of nitrogen. There could also be nitrogen immobilization that occurs when the winter rye cover crop decomposes. This is where soil microorganisms consume plant-available nitrogen (ammonium and nitrate) while decomposing the plant material, reducing the amount available for the corn crop in the soil. The more winter rye biomass there is, the more immobilization that can occur.

It’s important to note that the findings reported here are for late summer and early fall manure applications. There are still many aspects of cover crop use with manure that need to be fully explored, such as timing of manure application (in late fall or spring).

Cover crops and corn yield

Similar to our findings with nitrogen, risk of corn yield loss occurred when cover crop biomass exceeded 1,000 lbs./ac. The biggest effects were observed when winter rye exceeded 2,000 lbs./ac. For the most part, yield reductions were less than 10 bu/ac, and there were no observable nutrient deficiencies in the corn crop. Our findings are not unique, as others in the Midwest have found similar results.

In contrast, cover crop trials by the Practical Farmers of Iowa (PFI) have shown yield reductions to be rare, occurring in only two of 29 site years between 2011 and 2019. (The report can be found at www.practicalfarmers.org.) These studies by PFI were conducted with cooperating farmers on their fields. Collectively, this indicates that there is some potential risk to corn yield when winter rye biomass gets too high, but experience with cover crops can reduce the overall risk of yield loss.

Grass cover crops take up nitrogen from the manure that would have likely leached out of the root zone over winter and spring before planting. However, it does appear to tap into the nitrogen that would typically be available for that next corn crop. The trick for farmers is to grow enough cover crop biomass for good erosion control but not grow too much as to tie up nitrogen. See the sidebar for recommendations.

Cover crop recommendations

- If new to cover cropping, consider starting with spring barley or oats (covers that will winterkill in cold climates).

- Keep seeding rates low for covers that survive the winter (such as 60 lbs./ac or less for winter rye).

- Wait 10 to 14 days between termination of winter rye and corn planting.

- Utilize a starter fertilizer that contains nitrogen.

- Use row clear attachments on planters to increase soil warming around the seed.

- Split apply N fertilizer, or at least avoid having all of the nitrogen applied in-season.

- If a lot of biomass has already been produced during a warm fall, consider a fall termination to avoid excessive biomass in the spring.

- Terminate the winter rye as early in the spring as possible and make fields with an abundance of winter rye biomass top priority in the spring.

- Consider harvesting the winter rye as a winter silage crop. This would also be beneficial from a nutrient management planning perspective, as the nutrients from the fall manure application would be applied to this winter silage crop. If interested in this option, it will also be important to follow all herbicide rules, as some applications can prevent the winter rye from being fed.

- If you want to avoid risk, consider planting soybeans instead of corn.

This article appeared in the November 2020 issue of Journal of Nutrient Management on pages 6 to 8.

Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine.